FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

(Redirected from Question: Was Joseph Smith a "serial practitioner of statutory rape" or a "pedophile"?)

Summary: Helen was nearly fifteen when her father urged her to be sealed to Joseph Smith

The Prophet said...that it [plural marriage] would damn more than it would have because \so many/ unprincipled men would take advantage of it, but that did not prove that it was not a pure principle. If Joseph had had any impure desires he could have gratified them in the style of the world with less danger of his life or his character, than to do as he did. The Lord commanded him to teach & to practice that principle.

—Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, Letter to Mary Bond, n.d., 3-9 quoted in Brian Hales, Joseph Smith's Polygamy: History, Vol. 1, 26-27. off-site

Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior…Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards.[1]

—Lynn Hunt, President of American Historical Association

Some points regarding the circumstances surrounding the sealing of Helen Mar Kimball to Joseph Smith[2]:

During the winter of 1843, there were plenty of parties and balls. … Some of the young gentlemen got up a series of dancing parties, to be held at the Mansion once a week. … I had to stay home, as my father had been warned by the Prophet to keep his daughter away from there, because of the blacklegs and certain ones of questionable character who attended there. … I felt quite sore over it, and thought it a very unkind act in father to allow [my brother] to go and enjoy the dance unrestrained with others of my companions, and fetter me down, for no girl loved dancing better than I did, and I really felt that it was too much to bear. It made the dull school still more dull, and like a wild bird I longer for the freedom that was denied me; and thought myself a much abused child, and that it was pardonable if I did murmur.[8]

I am thankful that He [Heavenly Father] has brought me through the furnace of affliction and that He has condescended to show me that the promises made to me the morning that I was sealed to the Prophet of God will not fail and I would not have the chain broken for I have had a view of the principle of eternal salvation and the perfect union which this sealing power will bring to the human family and with the help of our Heavenly Father I am determined to so live that I can claim those promises.[14]

Later in life, Helen wrote a poem entitled "Reminiscences." It is often cited for the critics' claims:

The first portion of the poem expresses the youthful Helen's attitude. She is distressed mostly because of the loss of socialization and youthful ideas about romance. But, as Helen was later to explain more clearly in prose, she would soon realize that her youthful pout was uncalled for—she saw that her plural marriage had, in fact, protected her. "I have long since learned to leave all with Him, who knoweth better than ourselves what will make us happy," she noted after the poem.[16]

Thus, she would later write of her youthful disappointment in not being permitted to attend a party or dance:

I felt quite sore over it, and thought it a very unkind act in father to allow William to go and enjoy the dance unrestrained with other of my companions, and fetter me down, for no girl danced better than I did, and I really felt it was too much to bear. It made the dull school more dull, and like a wild bird I longed for the freedom that was denied me; and thought to myself an abused child, and that it was pardonable if I did not murmur.

I imagined that my happiness was all over and brooded over the sad memories of sweet departed joys and all manner of future woes, which (by the by) were of short duration, my bump of hope being too large to admit of my remaining long under the clouds. Besides my father was very kind and indulgent in other ways, and always took me with him when mother could not go, and it was not a very long time before I became satisfied that I was blessed in being under the control of so good and wise a parent who had taken counsel and thus saved me from evils, which some others in their youth and inexperience were exposed to though they thought no evil. Yet the busy tongue of scandal did not spare them. A moral may be drawn from this truthful story. "Children obey thy parents," etc. And also, "Have regard to thy name, for that shall continue with you above a thousand great treasures of gold." "A good life hath but few days; but a good name endureth forever.[17]

So, despite her youthful reaction, Helen uses this as an illustration of how she was being a bit immature and upset, and how she ought to have trusted her parents, and that she was actually protected from problems that arose from the parties she missed.

Critics of the Church provide a supposed "confession" from Helen, in which she reportedly said:

I would never have been sealed to Joseph had I known it was anything more than ceremony. I was young, and they deceived me, by saying the salvation of our whole family depended on it.[18]

Author Todd Compton properly characterizes this source, noting that it is an anti-Mormon work, and calls its extreme language "suspect."[19]

Author George D. Smith tells his readers only that this is Helen "confiding," while doing nothing to reveal the statement's provenance from a hostile source.[20] Newell and Avery tell us nothing of the nature of this source and call it only a "statement" in the Stanley Ivins Collection;[21] Van Wagoner mirrors G. D. Smith by disingenuously writing that "Helen confided [this information] to a close Nauvoo friend," without revealing its anti-Mormon origins.[22]

To credit this story at face value, one must also admit that Helen told others in Nauvoo about the marriage (something she repeatedly emphasized she was not to do) and that she told a story at variance with all the others from her pen during a lifetime of staunch defense of plural marriage.[23]

As Brian Hales writes:

It is clear that Helen’s sealing to Joseph Smith prevented her from socializing as an unmarried lady. The primary document referring to the relationship is an 1881 poem penned by Helen that has been interpreted in different ways:"I thought through this life my time will be my own The step I now am taking’s for eternity alone, No one need be the wiser, through time I shall be free, And as the past hath been the future still will be. To my guileless heart all free from worldly care And full of blissful hopes and youthful visions rare The world seamed bright the thret’ning clouds were kept From sight and all looked fair but pitying angels wept. They saw my youthful friends grow shy and cold. And poisonous darts from sland’rous tongues were hurled, Untutor’d heart in thy gen’rous sacrafise, Thou dids’t not weigh the cost nor know the bitter price; Thy happy dreams all o’er thou’st doom’d also to be Bar’d out from social scenes by this thy destiny, And o’er thy sad’nd mem’ries of sweet departed joys Thy sicken’d heart will brood and imagine future woes, And like a fetter’d bird with wild and longing heart, Thou’lt dayly pine for freedom and murmor at thy lot; But could’st thou see the future & view that glorious crown, Awaiting you in Heaven you would not weep nor mourn. Pure and exalted was thy father’s aim, he saw A glory in obeying this high celestial law, For to thousands who’ve died without the light I will bring eternal joy & make thy crown more bright. I’d been taught to reveire the Prophet of God And receive every word as the word of the Lord, But had this not come through my dear father’s mouth, I should ne’r have received it as God’s sacred truth."

One year after writing the above poem, she elaborated:

"During the winter of 1843, there were plenty of parties and balls. … Some of the young gentlemen got up a series of dancing parties, to be held at the Mansion once a week. … I had to stay home, as my father had been warned by the Prophet to keep his daughter away from there, because of the blacklegs and certain ones of questionable character who attended there. … I felt quite sore over it, and thought it a very unkind act in father to allow [my brother] to go and enjoy the dance unrestrained with others of my companions, and fetter me down, for no girl loved dancing better than I did, and I really felt that it was too much to bear. It made the dull school still more dull, and like a wild bird I longed for the freedom that was denied me; and thought myself a much abused child, and that it was pardonable if I did murmur."

After leaving the church, dissenter Catherine Lewis reported Helen saying: "I would never have been sealed to Joseph had I known it was anything more than a ceremony."

Assuming this statement was accurate, which is not certain, the question arises regarding her meaning of "more than a ceremony"? While sexuality is a possibility, a more likely interpretation is that the ceremony prevented her from associating with her friends as an unmarried teenager, causing her dramatic distress after the sealing.

Supporting that the union was never consummated is the fact that Helen Mar Kimball was not called to testify in the Temple Lot trial. In 1892, the RLDS Church led by Joseph Smith, III sued the Church of Christ (Hedrickites), disputing its claim to own the temple lot in Independence, Missouri, that Edward Partridge, acting for the church, had purchased in 1831 and which his widow, Lydia, had sold in 1848 to finance her family’s trek west.

The Hedrickites held physical possession, but the RLDS Church took the official position that, since it was the true successor of the church originally founded by Joseph Smith, it owned the property outright.[24]

Critics generally do not reveal that their sources have concluded that Helen's marriage to Joseph Smith was unconsummated, preferring instead to point out that mere fact of the marriage of a 14-year-old girl to a 37-year-old man ought to be evidence enough to imply sexual relations and "pedophilia." For example, George D. Smith quotes Compton without disclosing his view,[25] cites Compton, but ignores that Compton argues that " there is absolutely no evidence that there was any sexuality in the marriage, and I suggest that, following later practice in Utah, there may have been no sexuality. All the evidence points to this marriage as a primarily dynastic marriage." [26] and Stanley Kimball without disclosing that he believed the marriage to be "unconsummated." [27]

Critical sources |

|

Helen made clear what she disliked about plural marriage in Nauvoo, and it was not physical relations with an older man:

I had, in hours of temptation, when seeing the trials of my mother, felt to rebel. I hated polygamy in my heart, I had loved my baby more than my God, and mourned for it unreasonably….[28]

Helen is describing a period during the westward migration when (married monogamously) her first child died. Helen was upset by polygamy only because she saw the difficulties it placed on her mother. She is not complaining about her own experience with it.

Helen Mar Kimball:

All my sins and shortcomings were magnified before my eyes till I believed I had sinned beyond redemption. Some may call it the fruits of a diseased brain. There is nothing without a cause, be that as it may, it was a keen reality to me. During that season I lost my speech, forgot the names of everybody and everything, and was living in another sphere, learning lessons that would serve me in future times to keep me in the narrow way. I was left a poor wreck of what I had been, but the Devil with all his cunning, little thought that he was fitting and preparing my heart to fulfill its destiny….

[A]fter spending one of the happiest days of my life I was moved upon to talk to my mother. I knew her heart was weighed down in sorrow and I was full of the holy Ghost. I talked as I never did before, I was too weak to talk with such a voice (of my own strength), beside, I never before spoke with such eloquence, and she knew that it was not myself. She was so affected that she sobbed till I ceased. I assured her that father loved her, but he had a work to do, she must rise above her feelings and seek for the Holy Comforter, and though it rent her heart she must uphold him, for he in taking other wives had done it only in obedience to a holy principle. Much more I said, and when I ceased, she wiped her eyes and told me to rest. I had not felt tired till she said this, but commenced then to feel myself sinking away. I silently prayed to be renewed, when my strength returned that instant…

I have encouraged and sustained my husband in the celestial order of marriage because I knew it was right. At various times I have been healed by the washing and annointing, administered by the mothers in Israel. I am still spared to testify to the truth and Godliness of this work; and though my happiness once consisted in laboring for those I love, the Lord has seen fit to deprive me of bodily strength, and taught me to 'cast my bread upon the waters' and after many days my longing spirit was cheered with the knowledge that He had a work for me to do, and with Him, I know that all things are possible…[29]

Imagine a school-child who asks why French knights didn't resist the English during the Battle of Agincourt (in 1415) using Sherman battle tanks. We might gently reply that there were no such tanks available. The child, a precocious sort, retorts that the French generals must have been incompetent, because everyone knows that tanks are necessary. The child has fallen into the trap of presentism—he has presumed that situations and circumstances in the past are always the same as the present. Clearly, there were no Sherman tanks available in 1415; we cannot in fairness criticize the French for not using something which was unavailable and unimagined.

Spotting such anachronistic examples of presentism is relatively simple. The more difficult problems involve issues of culture, behavior, and attitude. For example, it seems perfectly obvious to most twenty-first century North Americans that discrimination on the basis of race is wrong. We might judge a modern, racist politician quite harshly. We risk presentism, however, if we presume that all past politicians and citizens should have recognized racism, and fought it. In fact, for the vast majority of history, racism has almost always been present. Virtually all historical figures are, by modern standards, racists. To identify George Washington or Thomas Jefferson as racists, and to judge them as moral failures, is to be guilty of presentism.

A caution against presentism is not to claim that no moral judgments are possible about historical events, or that it does not matter whether we are racists or not. Washington and Jefferson were born into a culture where society, law, and practice had institutionalized racism. For them even to perceive racism as a problem would have required that they lift themselves out of their historical time and place. Like fish surrounded by water, racism was so prevalent and pervasive that to even imagine a world without it would have been extraordinarily difficult. We will not properly understand Washington and Jefferson, and their choices, if we simply condemn them for violating modern standards of which no one in their era was aware.

Condemning Joseph Smith for "statutory rape" is a textbook example of presentist history. "Rape," of course, is a crime in which the victim is forced into sexual behavior against her (or his) will. Such behavior has been widely condemned in ancient and modern societies. Like murder or theft, it arguably violates the moral conscience of any normal individual. It was certainly a crime in Joseph Smith's day, and if Joseph was guilty of forced sexual intercourse, it would be appropriate to condemn him.

(Despite what some claim, not all marriages or sealings were consummated, as in Helen's case discussed above.)

"Statutory rape," however, is a completely different matter. Statutory rape is sexual intercourse with a victim that is deemed too young to provide legal consent--it is rape under the "statute," or criminal laws of the nation. Thus, a twenty-year-old woman who chooses to have sex has not been raped. Our society has concluded, however, that a ten-year-old child does not have the physical, sexual, or emotional maturity to truly understand the decision to become sexually active. Even if a ten-year-old agrees to sexual intercourse with a twenty-year-old male, the male is guilty of "statutory rape." The child's consent does not excuse the adult's behavior, because the adult should have known that sex with a minor child is illegal.

Even in the modern United States, statutory rape laws vary by state. A twenty-year-old who has consensual sex with a sixteen-year-old in Alabama would have nothing to fear; moving to California would make him guilty of statutory rape even if his partner was seventeen.

By analogy, Joseph Smith likely owned a firearm for which he did not have a license--this is hardly surprising, since no law required guns to be registered on the frontier in 1840. It would be ridiculous for Hitchens to complain that Joseph "carried an unregistered firearm." While it is certainly true that Joseph's gun was unregistered, this tells us very little about whether Joseph was a good or bad man. The key question, then, is not "Would Joseph Smith's actions be illegal today?" Only a bigot would condemn someone for violating a law that had not been made.

Rather, the question should be, "Did Joseph violate the laws of the society in which he lived?" If Joseph did not break the law, then we might go on to ask, "Did his behavior, despite not being illegal, violate the common norms of conscience or humanity?" For example, even if murder was not illegal in Illinois, if Joseph repeatedly murdered, we might well question his morality.

"Pedophilia" applies to children; Helen was regarded as a mature young woman

Helen specifically mentioned that she was regarded as mature.[30] 'Pedophilia' is an inflammatory charge that refers to a sexual attraction to pre-pubertal children. It simply does not apply in the present case, even if the relationship had been consummated.

We must, then, address four questions:

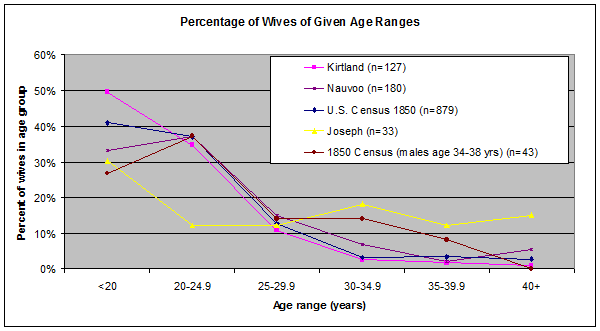

Even LDS authors are not immune from presentist fallacies: Todd Compton, convinced that plural marriage was a tragic mistake, "strongly disapprove[s] of polygamous marriages involving teenage women." [31] This would include, presumably, those marriages which Joseph insisted were commanded by God. Compton notes, with some disapproval, that a third of Joseph's wives were under twenty years of age. The modern reader may be shocked. We must beware, however, of presentism—is it that unusual that a third of Joseph's wives would have been teenagers?

When we study others in Joseph's environment, we find that it was not. A sample of 201 Nauvoo-era civil marriages found that 33.3% were under twenty, with one bride as young as twelve. [32] Another sample of 127 Kirtland marriages found that nearly half (49.6%) were under twenty. [33] And, a computer-aided study of LDS marriages found that from 1835–1845, 42.3% of women were married before age twenty. [34] The only surprising thing about Joseph's one third is that more of his marriage partners were not younger.

Furthermore, this pattern does not seem to be confined to the Mormons (see Chart 12 1). A 1% sample from the 1850 U.S. census found 989 men and 962 who had been married in the last year. Teens made up 36.0% of married women, and only 2.3% of men; the average age of marriage was 22.5 for women and 27.8 for men. [35] Even when the men in Joseph's age range (34–38 years) in the U.S. Census are extracted, Joseph still has a lower percentage of younger wives and more older wives than non-members half a decade later. [36]

I suspect that Compton goes out of his way to inflate the number of young wives, since he lumps everyone between "14 to 20 years old" together. [37] It is not clear why this age range should be chosen—women eighteen or older are adults even by modern standards.

A more useful breakdown by age is found in Table 12-1. Rather than lumping all wives younger than twenty-one together (a third of all the wives), our analysis shows that only a fifth of the wives would be under eighteen. These are the only women at risk of statutory rape issues even in the modern era.

| Age range | Percent (n=33) |

|---|---|

| 14-17 | 21.2% |

| 18-19 | 9.1% |

| 20-29 | 27.3% |

| 30-39 | 27.3% |

| 40-49 | 3.0% |

| 50-59 | 12.1% |

As shown elsewhere, the data for sexual relations in Joseph's plural marriages are quite scant (see Chapter 10—not online). For the purposes of evaluating "statutory rape" charges, only a few relationships are relevant.

The most prominent is, of course, Helen Mar Kimball, who was the prophet's youngest wife, married three months prior to her 15th birthday. [39] As we have seen, Todd Compton's treatment is somewhat confused, but he clarifies his stance and writes that "[a]ll the evidence points to this marriage as a primarily dynastic marriage." [40] Other historians have also concluded that Helen's marriage to Joseph was unconsummated. [41]

Nancy M. Winchester was married at age fourteen or fifteen, but we know nothing else of her relationship with Joseph. [42]

Flora Ann Woodruff was also sixteen at her marriage, and "[a]n important motivation" seems to have been "the creation of a bond between" Flora's family and Joseph. [43] We know nothing of the presence or absence of marital intimacy.

Fanny Alger would have been sixteen if Compton's date for the marriage is accepted. Given that I favor a later date for her marriage, this would make her eighteen. In either case, we have already seen how little reliable information is available for this marriage (see Chapter 4—not online), though on balance it was probably consummated.

Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Sarah Lawrence were each seventeen at the time of their marriage. Here at last we have reliable evidence of intimacy, since Lucy Walker suggested that the Lawrence sisters had consummated their marriage with Joseph. Intimacy in Joseph's marriages may have been more rare than many have assumed—Walker's testimony suggested marital relations with the Partridge and Lawrence sisters, but said nothing about intimacy in her own marriage (see Chapter 10—not online).

Sarah Ann Whitney's marriage had heavy dynastic overtones, binding Joseph to faithful Bishop Orson F. Whitney. We know nothing of a sexual dimension, though Compton presumes that one is implied by references to the couple's "posterity" and "rights" of marriage in the sealing ceremony. [44] This is certainly plausible, though the doctrine of adoption and Joseph's possible desire to establish a pattern for all marriages/sealings might caution us against assuming too much.

Of Joseph's seven under-eighteen wives, then, only one (Lawrence) has even second-hand evidence of intimacy. Fanny Alger has third-hand hostile accounts of intimacy, and we know nothing about most of the others. Lucy Walker and Helen Mar Kimball seem unlikely candidates for consummation.

The evidence simply does not support Christopher Hitchens' wild claim, since there is scant evidence for sexuality in the majority of Joseph's marriages. Many presume that Joseph practiced polygamy to satisfy sexual longings, and with a leer suggest that of course Joseph would have consummated these relationships, since that was the whole point. Such reasoning is circular, and condemns Joseph's motives and actions before the evidence is heard.

Even were we to conclude that Joseph consummated each of his marriages—a claim nowhere sustained by the evidence—this would not prove that he acted improperly, or was guilty of "statutory rape." This requires an examination into the legal climate of his era.

The very concept of a fifteen- or seventeen-year-old suffering statutory rape in the 1840s is flagrant presentism. The age of consent under English common law was ten. American law did not raise the age of consent until the late nineteenth century, and in Joseph Smith's day only a few states had raised it to twelve. Delaware, meanwhile, lowered the age of consent to seven. [45]

In our time, legal minors can often be married before the age of consent with parental approval. Joseph certainly sought and received the approval of parents or male guardians for his marriages to Fanny Alger, Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Helen Kimball. [46] His habit of approaching male relatives on this issue might suggest that permission was gained for other marriages about which we know less.

Clearly, then, Hitchens' attack is hopelessly presentist. None of Joseph's brides was near ten or twelve. And even if his wives' ages had presented legal risks, he often had parental sanction for the match.

There can be no doubt that the practice of polygamy was deeply offensive to monogamous, Victorian America. As everything from the Nauvoo Expositor to the latest anti-Mormon tract shows, the Saints were continually attacked for their plural marriages.

If we set aside the issue of plurality, however, the only issue which remains is whether it would have been considered bizarre, improper, or scandalous for a man in his mid-thirties to marry a woman in her mid- to late-teens. Clearly, Joseph's marriage to teen-age women was entirely normal for Mormons of his era. The sole remaining question is, were all these teen-age women marrying men their own age, or was marriage to older husbands also considered proper?

To my knowledge, the issue of age disparity was not a charge raised by critics in Joseph's day. It is difficult to prove a negative, but the absence of much comment on this point is probably best explained by the fact that plural marriage was scandalous, but marriages with teenage women were, if not the norm, at least not uncommon enough to occasion comment. For example, to disguise the practice of plural marriage, Joseph had eighteen-year-old Sarah Whitney pretend to marry Joseph Kingsbury, who was days away from thirty-one. [47] If this age gap would have occasioned comment, Joseph Smith would not have used Kingsbury as a decoy.

One hundred and eighty Nauvoo-era civil marriages have husbands and wives with known ages and marriage dates. [48] Chart 12 2 demonstrates that these marriages follow the general pattern of wives being younger than husbands.

When the age of husband is plotted against the age of each wife, it becomes clear that almost all brides younger than twenty married men between five and twenty years older (see Chart 12-3).

This same pattern appears in 879 marriages from the 1850 U.S. Census (see Chart 12 4). Non-Mormon age differences easily exceeded Joseph's except for age fourteen. We should not make too much of this, since the sample size is very small (one or two cases for Joseph; three for the census) and dynastic motives likely played a large role in Joseph's choice, as discussed above.

In short, Mormon civil marriage patterns likely mimicked those of their gentile neighbors. Neither Mormons or their critics would have found broad age differences to be an impediment to conjugal marriage. In fact, the age difference between wives and their husbands was greatest in the teen years, and decreased steadily until around Joseph's age, between 30–40 years, when the spread between spouses' ages was narrowest (note the bright pink bars in Chart 12-5).

As Thomas Hine, a non-LDS scholar of adolescence noted:

Why did pre-modern peoples see nothing wrong with teen marriages? Part of the explanation likely lies in the fact that life-expectancy was greatly reduced compared to our time (see Table 12 2).

| Group | Life Expect in 1850 (years) [50] | Life Expect in 1901 (years) [51] | Life Expect in 2004 (years) [52] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males at birth | 38.3 | 47.9 | 75.7 |

| Males at age 20 | 60.1 | 62.0 | 76.6 |

| Females at birth | 40.5 | 50.7 | 80.8 |

| Females at age 20 | 60.2 | 63.6 | 81.5 |

The modern era has also seen the "extension" of childhood, as many more years are spent in schooling and preparation for adult work. In the 1840s, these issues simply weren't in play for women—men needed to be able to provide for their future family, and often had the duties of apprenticeship which prevented early marriage. Virtually everything a woman needed to know about housekeeping and childrearing, however, was taught in the home. It is not surprising, then, that parents in the 1840s considered their teens capable of functioning as married adults, while parents in 2007 know that marriages for young teens will usually founder on issues of immaturity, under-employment, and lack of education.

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now