FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

< Countercult ministries | The Interactive Bible | Difficult Questions for Mormons

FAIR Answers—back to home page

| Book of Mormon Culture | A FAIR Analysis of: Difficult Questions for Mormons, a work by author: The Interactive Bible

|

Book of Mormon Animals |

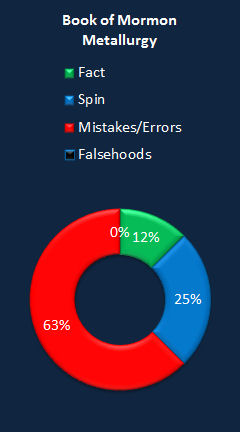

| Claim Evaluation |

| Difficult Questions for Mormons |

|

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention Bellows (1 Nephi 17:11)...? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention...Brass (2 Nephi 5:15)...? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

"Brass" is an alloy of copper and zinc. It is a term used frequently in the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Some occurrences in the Bible have been determined by Biblical scholars to actually reflect the use of bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), rather than brass.

On the other hand, actual brass has been found in the Old World which dates to Lehi's era, and so the idea of "brass" plates is not the anachronism which was once thought. Either "brass plates" or "bronze plates" would fit.[2]

An interesting point concerning alloys is found in Ether 10꞉23

in which the Jaredites "did make...brass," (an alloy), but "did dig...to get ore of gold, and of silver, and of iron, and of copper." The Book of Mormon author has a clear understanding of those metals which are found in a raw state, and those which must be made as an alloy.

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention...Breast Plates & Copper (Mosiah 8:10)...? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

Question: Is the mention of copper in the Book of Mormon an anachronism?

Book of Mormon armor does not match the type of armor that Joseph Smith would have been familiar with, nor does it reflect European styles of armor:

19 And when the armies of the Lamanites saw that the people of Nephi, or that Moroni, had prepared his people with breastplates and with arm–shields, yea, and also shields to defend their heads, and also they were dressed with thick clothing—Alma 43:19

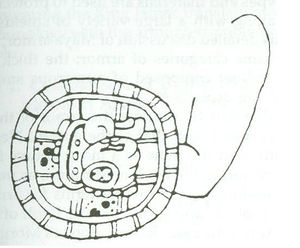

This description matches Mesoamerican quilted armor:

"The garment worn by this figure is believed to represent the quilted armor worn by warriors, but the elaboration of the costume and its accoutrements suggest a figure of high rank and noble status." Costumed Figure, 7th–8th century—Mexico; Maya Ceramic, pigment; H. 11 17/32 in. (29.3 cm) (1979.206.953) – Metropolitan Museum of Art Note the pectoral ("breast plate"). Note that this figure post-dates the Nephite period. |

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention...Iron (Jarom 1:8)...? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

John L. Sorenson:[3]

Iron use was documented in the statements of early Spaniards, who told of the Aztecs using iron-studded clubs. [4] A number of artifacts have been preserved that are unquestionably of iron; their considerable sophistication, in some cases, at least suggests interest in this metal [5]....Few of these specimens have been chemically analyzed to determine whether the iron used was from meteors or from smelted ore. The possibility that smelted iron either has been or may yet be found is enhanced by a find at Teotihuacan. A pottery vessel dating to about A.D. 300, and apparently used for smelting, contained a "metallic-looking" mass. Analyzed chemically, it proved to contain copper and iron. [6]

John L. Sorenson:

Without even considering smelted iron, we find that peoples in Mesoamerica exploited iron minerals from early times. Lumps of hematite, magnetite, and ilmenite were brought into Valley of Oaxaca sites from some of the thirty-six ore exposures located near or in the valley. These were carried to a workshop section within the site of San Jose Mogote as early as 1200 B.C. There they were crafted into mirrors by sticking the fragments onto prepared mirror backs and polishing the surface highly. These objects, clearly of high value, were traded at considerable distances.[7]

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention...Gold and Silver currency (Alma 11), Silver (Jarom 1:8)...? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

John Welch,

Midway through one of the most heart-wrenching accounts in the Book of Mormon, when Alma and Amulek were on trial for their lives and Amulek's faithful women and children were put to death by fire, the story is interrupted with an explanation of King Mosiah's system of weights and measures (see Alma 11:3–19). It is a strange interruption, a mundane hiatus, but at least a relieving diversion as the tension mounts in Alma and Amulek's showdown with Zeezrom and the legal officials in Ammonihah. Why would one bring up these incidental economic nuts and bolts at such a point in the record?

Several reasons might explain why this information was included at this point in the Book of Mormon. For one thing, these short metrological details are not only intertwined with the debate between Amulek and Zeezrom (see Alma 11:21–25), but they also provide an important building block in Mormon's grand narrative. By abusing the justice system and misusing the lawful weights and measures, the wicked people of Ammonihah effectively opened the floodgates of God's judgment upon themselves, a pattern that would apply later to Nephite civilization as a whole.

In addition, as this article will show, this sidelight in the book of Alma contains enough facts to support meaningful parallels between King Mosiah's weights and measures and those used in other ancient cultures. For many reasons, these monetary details found in the large plates are weighty matters indeed. The attempted bribery, the overreaching of the lawyers, the royal standardization and official codification of these measures, their mathematical relationships, and the unusual names involved in Alma 11 have long intrigued readers.[8]

It is claimed that Book of Mormon references to Nephite coins is an anachronism, as coins were not used either in ancient America or Israel during Lehi's day. One critical website even speculates: "Do you think that the Church just casually adds words to their sacred scriptures specifically for the purpose of summarizing and clarifying the text without being pretty confident they are doing so correctly?" [9]

The actual text of the 1830 Book of Mormon does not mention coins. The word "coins" was added in the 1920 edition to the chapter heading for Alma 11. In the 1948 edition of the Book of Mormon, we see the following chapter heading:

Judges and their compensation—Nephite coins and measures—Zeezrom confounded by Amulek

Seeing "coins" in the Book of Mormon occurs when readers apply their modern expectations and an inadequately close reading of the text. There are units of exchange (weight-based and tied to grain) in the Book of Mormon, but no coins.

Note the absence of the word "coins" from the chapter heading for Alma 11 found in the current edition of the Book of Mormon on the official Church website "lds.org":

The Nephite monetary system is set forth—Amulek contends with Zeezrom—Christ will not save people in their sins—Only those who inherit the kingdom of heaven are saved—All men will rise in immortality—There is no death after the Resurrection. About 82 B.C.

The pieces of gold and silver described in Alma 11꞉1-20

are not coins, but a surprisingly sophisticated [10] system of weights and measures that is consistent with Mesoamerican proto-monetary practices. [11] BYU Professor Daniel C. Peterson notes,

It is, alas, quite true that there is no evidence whatsoever for the existence of Book of Mormon coins. Not even in the Book of Mormon itself. The text of the Book of Mormon never mentions the word 'coin' or any variant of it. The reference to 'Nephite coinage' in the chapter heading to Alma 11 is not part of the original text, and is mistaken. Alma 11 is almost certainly talking about standardized weights of metal—a historical step toward coinage, but not yet the real thing" [12]

The chapter headings are not part of the inspired text. Elder Bruce R. McConkie, who composed the chapter headings for the heavily revised 1981 edition of the LDS scriptures, said:

[As for the] Joseph Smith Translation items, the chapter headings, Topical Guide, Bible Dictionary, footnotes, the Gazetteer, and the maps. None of these are perfect; they do not of themselves determine doctrine; there have been and undoubtedly now are mistakes in them. Cross-references, for instance, do not establish and never were intended to prove that parallel passages so much as pertain to the same subject. They are aids and helps only. [13]

Some critics have attempted to argue that the text's reference to "different pieces of their gold, and of their silver, according to their value," means that these were, in fact, coins. In short, they read this as a reference to "gold and silver pieces [i.e., coins]."

Such critics ignore that "pieces of gold and silver" is not necessarily the same as "gold pieces" or "silver pieces." They have not paid close attention to the text.

John L. Sorenson noted in 1985:

Most recently a burial containing 12,000 pieces of metal "money" (though not coins as such) was found in Ecuador, for the first time confirming that some ancient South Americans had the idea of accumulating a fortune in more or less standard units of metal wealth. Such a startling find in Mesoamerica could change our present limited ideas. [14]

Here we see that "pieces of metal" can act as a unit of exchange without being "coins."

Likewise, Webster's 1828 dictionary mentions coins as a possible use of the word in the eighth definition. But, earlier definitions do not require the application to coinage:

1. A fragment or part of any thing separated from the whole, in any manner, by cutting, splitting, breaking or tearing; as, to cut in pieces, break in pieces, tear in pieces, pull in pieces, &c.; a piece of a rock; a piece of paper.

2. A part of any thing, though not separated, or separated only in idea; not the whole; a portion; as a piece of excellent knowledge.

3. A distinct part or quantity; a part considered by itself, or separated from the rest only by a boundary or divisional line; as a piece of land in the meadow or on the mountain.

4. A separate part; a thing or portion distinct from others of a like kind; as a piece of timber; a piece of cloth; a piece of paper hangings. [15]

Clearly, any of these definitions could apply to standard weights of precious metal used in exchange. (It is interesting to note that by 1913, Webster's dictionary shifted the definition involving coins to third place: a suggestion that use of the term may have evolved.)

For example, Brigham Young observed in 1855:

a very ignorant person would know no difference between a piece of gold and a piece of bright copper. [16]

Gold or copper coins could easily be told apart because they are minted to appear different from each other. By contrast, the raw metal gold and bright (i.e., shiny, like gold) copper could be confused.

Writing in the early 1900s, B.H. Roberts said of the California gold rush:

Hudson picked out one piece of gold worth six dollars. [17]

Here we have a "piece of gold" (not "a gold piece") and a value given to it—but this is only raw gold, found and valued without any human coining or refining: it is simply the weight of raw metal. Andrew Jensen likewise wrote of "Mormon Island" in California:

On the 24th of January, 1848, Mr. James W. Marshall discovered a few pieces of gold in a mill race which had just been dug by members of the Mormon Battalion, who had recently received an honorable discharge from military service. [18]

Again, this raw gold is not coined.

Response to claim: "Why does the Book of Mormon mention...Steel Swords (Ether 7:9)? No evidence indicates that these items existed during Book of Mormon times."

The steel of the Book of Mormon is probably not modern steel. Steel, as we understand today, had to be produced using a very cumbersome process and was extremely expensive until the development of puddling towards the end of the 18th century. Even in ancient times, however, experienced smiths could produce steel by heating and hammering pig-iron or, earlier still, the never-molten iron from a bloomery to loose the surplus of carbon to get something like elastic steel. Early smiths even knew that by quenching hot steel in water, oil, or a salt solution the surface could be hardened.

Any Mesoamerican production likely depended upon the first method, which requires lower temperatures and less sophistication. Laban's "steel sword" is not anachronistic; Middle Eastern smiths were making steel by the tenth century B.C.[19]

Robert Maddin, James D. Muhly and Tamara S. Wheeler:

It seems evident that by the beginning of the tenth century B.C. blacksmiths were intentionally steeling iron. [20]

Matthew Roper:

Archaeologists, for example, have discovered evidence of sophisticated iron technology from the island of Cyprus. One interesting example was a curved iron knife found in an eleventh century tomb. Metallurgist Erik Tholander analyzed the weapon and found that it was made of “quench-hardened steel.” Other examples are known from Syro-Palestine. For example, an iron knife was found in an eleventh century Philistine tomb showed evidence of deliberate carburization. Another is an iron pick found at the ruins of an fortress on Mount Adir in northern Galilee and may date as early as the thirteenth century B.C. “The manufacturer of the pick had knowledge of the full range of iron-working skills associated with the production of quench hardened steel” (James D. Muhly, “How Iron technology changed the ancient world and gave the Philistines a military edge,” Biblical Archaeology Review 8/6 [November-December 1982]: 50). According to Amihai Mazar this implement was “made of real steel produced by carburizing, quenching and tempering.” (Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. New York: Doubleday, 1990, 361).[21]

Matthew Roper:

More significant, perhaps, in relation to the sword of Laban, archaeologists have discovered a carburized iron sword near Jericho. The sword which had a bronze haft, was one meter long and dates to the time of king Josiah, who would have been a contemporary of Lehi. This find has been described as “spectacular” since it is apparently “the only complete sword of its size and type from this period yet discovered in Israel.”(Hershall Shanks, “Antiquities director confronts problems and controversies,” Biblical Archaeology Review 12/4 [July-August 1986]: 33, 35).

Today the sword is displayed at Jerusalem’s Israel Museum. For a photo of the sword see the pdf version of the article here.

The sign on the display reads:

This rare and exceptionally long sword, which was discovered on the floor of a building next to the skeleton of a man, dates to the end of the First Temple period. The sword is 1.05 m. long (!) and has a double edged blade, with a prominent central ridge running along its entire length.

The hilt was originally inlaid with a material that has not survived, most probably wood. Only the nails that once secured the inlays to the hilt can still be seen. The sword’s sheath was also made of wood, and all that remains of it is its bronze tip. Owing to the length and weight of the sword, it was probably necessary to hold it with two hands. The sword is made of iron hardened into steel, attesting to substantial metallurgical know-how. Over the years, it has become cracked, due to corrosion.

Such discoveries lend a greater sense of historicity to Nephi’s passing comment in the Book of Mormon.[22]

Here is a video explanation and visual representation of this sword

John L. Sorenson: [23]

Steel is "iron that has been combined with carbon atoms through a controlled treatment of heating and cooling." [24] Yet "the ancients possessed in the natural (meteoric) nickel-iron alloy a type of steel that was not manufactured by mankind before 1890." [25] (It has been estimated that 50,000 tons of meteoritic material falls on the earth each day, although only a fraction of that is recoverable.) [26] By 1400 BC, smiths in Armenia had discovered how to carburize iron by prolonged heating in contact with carbon (derived from the charcoal in their forges). This produced martensite, which forms a thin layer of steel on the exterior of the object (commonly a sword) being manufactured. [27] Iron/steel jewelry, weapons, and tools (including tempered steel) were definitely made as early as 1300 BC (and perhaps earlier), as attested by excavations in present-day Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and Jordan. [28] "Smiths were carburizing [i.e., making steel] intentionally on a fairly large scale by at least 1000 BC in the Eastern Mediterranean area." [29]

William Hamblin: [30]

Steel is mentioned only five times in the Book of Mormon, once in the Book of Ether (7.9), and four times in the Nephite records (1 Ne 4.9, 1 Ne 16.18, 2 Ne 5.15 and Jar 1.8). Of these, two refer to Near Eastern weapons of the early sixth century B.C. 1 Ne 4.9 states that the blade of Laban’s sword was “of most precious steel.” Nephi’s Near Eastern bow was “made of fine steel” (1 Ne 16.18). The next two references are to steel among generic metal lists. The first is to the time of Nephi, around 580 B.C.:

“work in all manner of wood, and of iron, and of copper, and of brass, and of steel, and of gold, and of silver, and of precious ores” (2 Ne 5:15)

The second is from Jarom 1:8, around 400 B.C.:

“workmanship of wood, in buildings, and in machinery, and also in iron and copper, and brass and steel, making all manner of tools of every kind to till the ground, and weapons of war–yea, the sharp pointed arrow, and the quiver, and the dart, and the javelin, and all preparations for war”

Notice that these two texts are what is called a “literary topos,” meaning a stylized literary description which repeats the same ideas, events, or items in a standardized way in the same order and form.

Nephi: “wood, and of iron, and of copper, and of brass, and of steel” Jarom: “wood, …iron and copper, and brass and steel” The use of literary topoi is a fairly common ancient literary device found extensively in the Book of Mormon (and, incidentally, an evidence for the antiquity of the text). Scholars are often skeptical about the actuality behind a literary topos; it is often unclear if it is merely a literary device or is intended to describe specific unique circumstances.

Note, also, that although Jarom mentions a number of “weapons of war,” this list notably leaves off swords. Rather, it includes “arrow, and the quiver, and the dart, and the javelin.” If iron/steel swords were extensively used by Book of Mormon armies, why are they notably absent from this list of weapons, the only weapon-list that specifically mentions steel?

Significantly, there are no references to Nephite steel after 400 B.C.

Response to claim: "Tom Ferguson: 'Metallurgy does not appear in the region until about the 9th century A.D.'"

It is important first of all to realize that the Book of Mormon tends to use metals as sources of wealth and for ornamentation, and relatively rarely for 'prestige' weapons (e.g. sword of Laban) or items (e.g. metal plates for sacred records). It does not appear that Nephite society had as extensive a use of metal as the Middle East of the same time period. Attempting to insist otherwise misrepresents the Book of Mormon.

The Old World that Lehi and his family came from was certainly familiar with metal working. Nephi appears to have a direct knowledge of it. However, when they went to the New World, things changed and what metal working that Nephi knew did not start a revolution in the way buildings or anything else was built. Why?

Jared Diamond discusses some of the issues of cultural diffusion (and loss of information) in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel. There is simply no historical evidence that an innovation that exists in one place will necessarily carry over to a new location. In fact, there are places where important innovations used to exist and were lost. That tells us that we must not make unwarranted assumptions about the automatic transfer of Old World capabilities to the New.

Quoth Diamond:

The importance of diffusion, and of geographic location in making it possible, is strikingly illustrated by some otherwise incomprehensible cases of societies that abandoned powerful technologies. We tend to assume that useful technologies, once acquired, inevitably persist until superseded by better ones. In reality, technologies must be not only acquired but also maintained, and that too depends on many unpredictable factors. Any society goes through social movements or fads, in which economically useless things become valued or useful things devalued temporarily. Nowadays, when almost all societies on Earth are connected to each other, we cannot imagine a fad's going so far that an important technology would actually be discarded. A society that temporarily turned against a powerful technology would continue to see it being used by neighboring societies and would have the opportunity to reacquire it by diffusion (or would be conquered by neighbors if it failed to do so). But such fads can persist in isolated societies.[31]

The Book of Mormon reports that Laban had a steel sword. Steel weapons are known from this period in the ancient near east. (See Anonymous, "Out of the Dust: Ancient Steel Sword Unearthed," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14/2 (2005). [64–64] link)

Wrought iron heated in contact with charcoal (carbon) at high temperature produces carbonized iron or steel, which is more malleable than cast iron. Steel can be hardened by quenching (practiced as early as the tenth century B.C.E.), that is, cooling off the red-hot steel by sudden immersion into a vat of cold liquid. . . . At Har Adir in Upper Galilee, a remarkably well-preserved "steel pick" with an oak handle within the socket was found in an eleventh-century B.C.E. fortress. It was made of carburized iron (steel) that had been quenched and then tempered. This extraodinary artifact, one of the earliest known examples of steel tools, is a tribute to the skill (or luck) of the artisans of ancient Palestine.[32]

The next problem is the New World itself. There were two things retarding the use of metals in Mesoamerica. One is the availability of obsidian. Both for technical and sacred reasons, it was the cutting tool of choice. As a cutting tool, it was vastly superior to metal blades (rivaling modern surgical instruments). There was no need to look for a better blade, because they already had it.

The second is that the majority of metals available (a factor that continued through the time of the Spanish Conquest) were best suited for decorative purposes, not functional ones. There was gold and silver, but these were too soft for functional implements. When they were used, it was for artistic purposes.

In the Book of Mormon the strongest textual evidence for metalworking is the presence of gold plates. That fits the bill of the softer metal, not a functional one. Most of the described ores (save iron—see below) are soft metals. Mesoamerica did use quite a bit of iron ore, but much of it was used without smelting, establishing a cultural/religious connotation that would have retarded experimentation with the ore for any other purpose (ascription of religious value to any physical artifact delays changes in that artifact—see Amish clothing as a more modern example).

The 'conventional wisdom' that metal was not used in the New World prior to A.D. 900 cannot now be sustained. Copper sheathing on an altar in the Valley of Mexico dates to the first century B.C. [33] Furthermore, in 1998, a discovery in Peru pushed the earliest date of hammered metal back to as early as 1400 B.C.:

"Much to the surprise of archaeologists, one of the earliest civilizations in the Americas already knew how to hammer metals by 1000 B.C., centuries earlier than had been thought.

"Based on the dating of carbon atoms attached to the foils, they appear to have been created between 1410 and 1090 B.C., roughly the period when Moses led the Jews from Egypt and the era of such pharaohs as Amenhotep III, Tutankhamen and Ramses. 'It shows once again how little we know about the past and how there are surprises under every rock,' comments Jeffrey Quilter, director of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, a Harvard University research institute in Washington, D.C."[34]

Sorenson also adduces evidence for metals and metalwork through linguistic evidence. Many Mesoamerican languages have words for metals at very early dates; it would be very strange to have a word for something that one did not have or know existed! Some examples:[35]

| Language | Date of term for metal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As one non-LDS author wrote:

Current information clearly indicates that by 1000 B.C. the most advanced metallurgy was being practiced in the Cauca Valley of Colombia.[36]

Metallurgy is known in Peru from 1900 B.C., and in Ecuador via trade by 1000 B.C. Since Mesoamerica is known to have had trade relations with parts of the continent that produced metals, and because metal artifacts dating prior to A.D. 900 have been found in Mesoamerica, it seems reasonable to assume that at least some Mesoamericans knew something about metallurgy.

As John Sorensen, who worked with Ferguson, recalled:

[Stan] Larson implies that Ferguson was one of the "scholars and intellectuals in the Church" and that "his study" was conducted along the lines of reliable scholarship in the "field of archaeology." Those of us with personal experience with Ferguson and his thinking knew differently. He held an undergraduate law degree but never studied archaeology or related disciplines at a professional level, although he was self-educated in some of the literature of American archaeology. He held a naive view of "proof," perhaps related to his law practice where one either "proved" his case or lost the decision; compare the approach he used in his simplistic lawyerly book One Fold and One Shepherd. His associates with scientific training and thus more sophistication in the pitfalls involving intellectual matters could never draw him away from his narrow view of "research." (For example, in April 1953, when he and I did the first archaeological reconnaissance of central Chiapas, which defined the Foundation's work for the next twenty years, his concern was to ask if local people had found any figurines of "horses," rather than to document the scores of sites we discovered and put on record for the first time.) His role in "Mormon scholarship" was largely that of enthusiast and publicist, for which we can be grateful, but he was neither scholar nor analyst.

Ferguson was never an expert on archaeology and the Book of Mormon (let alone on the book of Abraham, about which his knowledge was superficial). He was not one whose careful "study" led him to see greater light, light that would free him from Latter-day Saint dogma, as Larson represents. Instead he was just a layman, initially enthusiastic and hopeful but eventually trapped by his unjustified expectations, flawed logic, limited information, perhaps offended pride, and lack of faith in the tedious research that real scholarship requires. The negative arguments he used against the Latter-day Saint scriptures in his last years display all these weaknesses.

Larson, like others who now wave Ferguson's example before us as a case of emancipation from benighted Mormon thinking, never faces the question of which Tom Ferguson was the real one. Ought we to respect the hard-driving younger man whose faith-filled efforts led to a valuable major research program, or should we admire the double-acting cynic of later years, embittered because he never hit the jackpot on, as he seems to have considered it, the slot-machine of archaeological research? I personally prefer to recall my bright-eyed, believing friend, not the aging figure Larson recommends as somehow wiser. [37]

Daniel C. Peterson and Matthew Roper: [38]

"Thomas Stuart Ferguson," says Stan Larson in the opening chapter of Quest for the Gold Plates, "is best known among Mormons as a popular fireside lecturer on Book of Mormon archaeology, as well as the author of One Fold and One Shepherd, and coauthor of Ancient America and the Book of Mormon" (p. 1). Actually, though, Ferguson is very little known among Latter-day Saints. He died in 1983, after all, and "he published no new articles or books after 1967" (p. 135). The books that he did publish are long out of print. "His role in 'Mormon scholarship' was," as Professor John L. Sorenson puts it, "largely that of enthusiast and publicist, for which we can be grateful, but he was neither scholar nor analyst." We know of no one who cites Ferguson as an authority, except countercultists, and we suspect that a poll of even those Latter-day Saints most interested in Book of Mormon studies would yield only a small percentage who recognize his name. Indeed, the radical discontinuity between Book of Mormon studies as done by Milton R. Hunter and Thomas Stuart Ferguson in the fifties and those practiced today by, say, the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) could hardly be more striking. Ferguson's memory has been kept alive by Stan Larson and certain critics of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as much as by anyone, and it is tempting to ask why. Why, in fact, is such disproportionate attention being directed to Tom Ferguson, an amateur and a writer of popularizing books, rather than, say, to M. Wells Jakeman, a trained scholar of Mesoamerican studies who served as a member of the advisory committee for the New World Archaeological Foundation?5 Dr. Jakeman retained his faith in the Book of Mormon until his death in 1998, though the fruit of his decades-long work on Book of Mormon geography and archaeology remains unpublished.

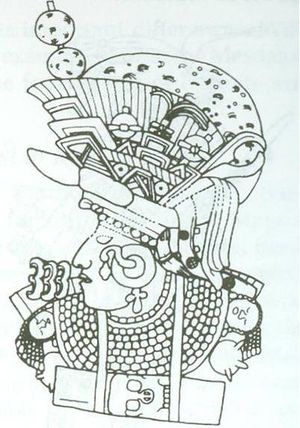

Response to claim: "Why doesn't the art (which is abundant) of the supposed Book of Mormon cultures portray the existence of metallurgical products or metallurgical activity?"

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now