FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

< Joseph Smith | Polygamy

FAIR Answers—back to home page

| Polygamy Book (draft chapters), a work by author: Gregory L. Smith

|

The charges are all late, at least second-hand, and typically gathered with hostile intent. Those making the claims are often verifiably wrong on other facts. The witnesses contradict each other, are sometimes ridiculous, and seem to be nothing but warmed-over gossip. Those who could have confirmed the stories did not. Many details bear the mark of outright fabrication.

Even more significantly, there is no contemporary account of witnesses accusing Joseph of unchastity in the Church's early years, save a single, second-or-third hand charge that was neither substantiated by those with an opportunity to do so, or repeated. Everything else is after-the-fact, often decades later. Given how anxious Joseph's enemies were to condemn him, it would be astonishing if he was known to be immoral without them noticing and taking advantage.

An early date for the first plural marriage revelation (see here) makes it more difficult for critics to charge that Joseph invented the idea of plural marriage to justify his "adultery" with Fanny Alger (see here). In response, some critics have charged that Joseph had a long history of adulterous scrapes predating 1831.

They want Joseph to be seen as a rake and womanizer. But was he?

Joseph Smith faced intense opposition throughout his life. Attacks on his moral character surfaced a few years after the Church's organization, though no such charges appeared before the organization of the Church.

A key source for these claims was an apostate Mormon, Doctor Philastus Hurlbut. Hurlbut joined the Church in 1833, but was excommunicated for immoral conduct while on a mission. Hurlbut became Joseph's avowed enemy, and Joseph even brought a peace warrant (akin to our modern "restraining order") against him because of threats on Joseph's life.

Hurlbut returned to the New York area, and gathered a collection of affidavits about Joseph and the Smith family. Hurlbut's reputation, however, was so notorious, that he gave the affidavits to Eber D. Howe of Painsville, Ohio. Howe disliked the Mormons, doubtless partly because his wife and daughter had joined the Church. Howe published the first anti-Mormon book using the affidavits: Mormonism Unvailed (1834).[2]

The Hurlbut-Howe affidavits have provided much anti-Mormon ammunition ever since. But, their value as historical documents is limited. There is evidence that Hurlbut influenced those who gave affidavits, and since some who gave them were illiterate, they may have merely signed statements written by Hurlbut himself.

That said, these charges continue to surface, and are sometimes used as a type of "introduction" to plural marriage. Critics seem to presume that because charges were made, those charges must be true to some extent—"where there's smoke, there must be at least a small fire." They then conclude that since these charges are true, they help explain Joseph's enthusiasm for plural marriage. It is difficult to prove a negative, but a great deal of doubt can be cast on the affidavits themselves, without even considering the bias and hatred which motivated their collection and publication.

One affidavit was provided by Levi Lewis, Emma Hale Smith's cousin and son of the Reverend Nathaniel Lewis, a well-known Methodist minister in Harmony.[3] Van Wagoner uses this affidavit to argue that:

[Joseph’s] abrupt 1830 departure with his wife, Emma, from Harmony, Pennsylvania, may have been precipitated in part by Levi and Hiel Lewis's accusations that Smith had acted improperly towards a local girl. Five years later Levi Lewis, Emma's cousin, repeated stories that Smith attempted to "seduce Eliza Winters &c.," and that both Smith and his friend Martin Harris had claimed "adultery was no crime." [4]

Van Wagoner argues that this "may" have been why Joseph left. But, we have no evidence of Levi and Hiel Lewis making the charge until the affidavits were gathered five years later. (Hiel Lewis' inclusion adds nothing; he gave no affidavit in 1833, and in 1879 simply repeated third hand stories of how Joseph had attempted to "seduce" Eliza.[5] At best, he is repeating Levi's early tale.)

A look at Lewis' complete affidavit is instructive. He claimed, among other things, that:

There are serious problems with these claims. It seems extraordinarily implausible that Joseph "admitted" that God had deceived him, and thus was not able to show the plates to anyone. Joseph insisted that he had shown the plates to people, and the Three and Eight Witnesses all published testimony to that effect. Despite apostasy and alienation from Joseph Smith, none denied that witness.

The claim to have seen Joseph drunk during the translation is entertaining. If Joseph were drunk, this only makes the production of the Book of Mormon more impressive. But, this sounds like little more than idle gossip, designed to bias readers against Joseph as a "drunkard."

A study of Joseph's letters and life from this period make it difficult to believe that Joseph would insist he was "as good as Jesus Christ." Joseph's private letters reveal him to be devout, sincere, and almost painfully aware of his dependence on God.[6]

Thus, three of the charges that are unmentioned by Van Wagoner are extraordinarily implausible. They are clearly efforts to simply paint Joseph in a bad light: make him into a pretend prophet who thinks he's better than Jesus, who admits to being deceived, and who gets drunk. Such a portrayal would be welcome to skeptical ears. This Joseph is ridiculous, not to be taken seriously.

We can now consider the claim that Martin and Joseph claimed that adultery was no crime, and that Joseph attempted the seduction of Eliza Winters. Recent work has also uncovered Eliza Winters' identity. She was a young woman at a meeting on 1 November 1832 in Springville Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania. While on a preaching mission with his brother Emer, Martin Harris announced that Eliza "has had a bastard child."

Eliza sued Martin for slander, asking for $1000 for the damage done to her "good name, fame, behavior and character" because his words "render her infamous and scandalous among her neighbors." Martin won the suit; Eliza could not prove libel, likely because she had no good character to sully.[7]

This new information calls the Lewis affidavit into even greater question. We are to believe that Martin, who risked and defended a libel suit for reproving Eliza for fornication, thinks that adultery is "no crime"? Eliza clearly has no reason to like Joseph and the Mormons—why did she not provide Hurlbut with an affidavit regarding Joseph's scandalous behavior? Around 1879, Eliza gave information to Frederick Mather for a book about early Mormonism. Why did she not provide testimony of Joseph's attempt to seduce her?

It seems far more likely that Eliza was known for her low morals, and her name became associated with the Mormons in popular memory, since she had been publicly rebuked by a Mormon preacher and lost her court suit against him. When Levi Lewis was approached by Hurlbut for material critical of Joseph Smith, he likely drew on this association.

Van Wagoner describes another charge against Joseph:

There is more to the story than this, however—much more. Van Wagoner even indicates that it is "unlikely" that "an incident between Smith and Nancy Johnson precipitated the mobbing." Unfortunately, Van Wagoner tucks this information into an endnote, where the reader will be unaware of it unless he checks the sources carefully.

Todd Compton casts further doubt on this episode. He notes that Van Wagoner's source is Fawn Brodie, and Brodie's source is from 1884—quite late. Clark Braden, the source, also got his information second-hand, and is clearly antagonistic, since he is a member of the Church of Christ, the “Disciples,” seeking to attack the Reorganized (RLDS) Church.[8] Brodie also gets the woman's name wrong—it is "Marinda Nancy," not "Nancy Marinda." And, the account is further flawed because Marinda has no brother named Eli.[9]

Compton notes further that there are two other late anti-Mormon sources that do not agree with the "Joseph as womanizer" version. Symonds Ryder, the leader of the attack, said that the attack occurred because of "the horrid fact that a plot was laid to take their property from them and place it under the control of Smith." [10] The Johnson boys are not portrayed as either leaders, or particularly hostile to Joseph. It is also unlikely that the mob would attack Sidney Rigdon as well as Joseph if the issue was one of their sister's honor, yet as Rigdon's son told the story, Sidney was the first target who received much harsher treatment:

Sidney was attacked until the mob thought he was dead; Joseph seems almost an after-thought in this version: someone they will pound until tired, while Sidney is beaten until thought dead.[11]

Marinda Johnson had difficulties with plural marriage, but many years later would still testify, "Here I feel like bearing my testimony that during the whole year that Joseph was an inmate of my father’s house I never saw aught in his daily life or conversation to make me doubt his divine mission." [12]

It is clear, then, that little remains of this episode to condemn Joseph—and Van Wagoner seems to think so too, though he caches this fact in the endnotes.

Van Wagoner continues to outline Joseph's supposed pattern of problems with women:

Benjamin F. Winchester,[13] Smith's close friend and leader of Philadelphia Mormons in the early 1840s, later recalled Kirtland accusations of scandal and "licentious conduct" hurled against Smith, "this more especially among the women. Joseph's name was connected with scandalous relations with two or three families."

There is again more to the story, and Van Wagoner again places it in the endnotes. Far from being a "close friend" of Joseph when he made the statement, Winchester was excommunicated after the martyrdom. Winchester claims he was excommunicated for being "[a] deadly enemy of the spiritual wife system and for this opposition he had received all manner of abuse from all who believe in that hellish system."

So, we have a late reminiscence, by someone who is now definitely not a “close friend and leader of Philadelphia Mormons” as he was in 1844. By his own admission, he was an excommunicate apostate and bitter opponent of plural marriage. And, all he can tell us is about rumors of “scandal” in Kirtland, and isn't even sure with whom or how many families.

Van Wagoner's habit of putting important details in the endnotes should trouble us more than these vague charges against Joseph in Kirtland—a period by which he had begun to practice plural marriage.

Winchester's other claims are not included by Van Wagoner. As with Levi Lewis' charges, the other claims demonstrate how unreliable Winchester is. He wrote that the Kirtland Temple dedication "ended in a drunken frolic." As one historian noted:

Such an accusation conflicts with many other contemporary accounts and is inconsistent with the Latter-day Saint attitude toward intemperance. If such behavior had been manifest, individuals would have undoubtedly recorded the information in their diaries or letters in 1836, but the negative reports emerged long after the events had transpired and among vindictive critics who had become enemies of the Church.

So, on issues which we can verify, Winchester is utterly unreliable. Why ought we to credit his vague, gossipy recall of early plural marriage?

The "best" sources on Joseph's early character have already been presented. The most creative, however, involves Polly Beswick, "a colorful two-hundred-pound Smith [servant who] told her friends" a tale better suited to a farce or bad situation comedy:

"Jo Smith said he had a revelation to lie with Vienna Jacques, who lived in his family" and that Emma Smith told her "Joseph would get up in the night and go to Vienna's bed." Furthermore, she added, "Emma would get out of humor, fret and scold and flounce in the harness," then Smith would "shut himself up in a room and pray for a revalation … state it to her, and bring her around all right."

One hardly knows where to start with this account. Van Wagoner notes that the story is second hand, but fails to mention that Polly is a known gossip. There is also no reference for Polly's claims—it is impossible to verify them, or know in what context they were given.

The description, however, seems totally implausible. No doubt, Emma Smith was challenged by plural marriage (see here). But, the image of Emma being petulant and then settling down once Joseph produces a "revalation" is totally out of character and quite different from how she behaved when Joseph did provide a revelation. I find this evidence utterly unconvincing and unreliable.

The final source provided by Van Wagoner quotes Martin Harris from an interview purportedly given in 1873:

Martin Harris, Book of Mormon benefactor and close friend of Smith, recalled another such incident from the early Kirtland period. "In or about the year 1833," Harris remembered, Joseph Smith's "servant girl“ claimed that the prophet had made "improper proposals to her, which created quite a talk amongst the people." When Smith came to him for advice, Harris, supposing that there was nothing to the story, told him to "take no notice of the girl, that she was full of the devil, and wanted to destroy the prophet of god." But according to Harris, Smith "acknowledged that there was more truth than poetry in what the girl said." Harris then said he would have nothing to do with the matter; Smith could get out of the trouble "the best way he knew how" [14]

We should not be surprised by now that this charge has many weaknesses. To begin with, Martin Harris was not in Kirtland at the time. The interview with Martin Harris supposedly occurred in 1873; it was not published until 1888. The reader's patience is also strained when we realize that Harris had returned to the Church by 1870, and died 10 June 1875 before the interview was published. Why would Harris give a "tell-all" interview about Joseph Smith three years after being rebaptized and endowed? He was safely dead before it was published, so the author had no need to worry about Harris' reaction.

Furthermore, in this account Martin Harris is portrayed as someone who definitely did not approve of adulterous conduct. This is in direct contradiction with the Levi Lewis affidavit, which has Harris claiming that adultery is no crime.

Though there are no contemporary witnesses of Joseph's bad behavior, there are witnesses to his good character. We have already seen how Marinda Nancy Johnson also testified of Joseph's good conduct, but there are other more contemporary witnesses.

Two of Josiah Stowell's daughters (probably Miriam and Rhoda) were called during a June 1830 court case against Joseph:

the court was detained for a time, in order that two young women (daughters to Mr. Stoal) with whom I had at times kept company; might be sent for, in order, if possible to elicit something from them which might be made a pretext against me. The young ladies arrived and were severally examined, touching my character, and conduct in general but particularly as to my behavior towards them both in public and private, when they both bore such testimony in my favor, as left my enemies without a pretext on their account.[15]

Notes

Summary: Critics charge that Joseph Smith performed monogamous marriages for time of already-married members, violating Ohio law in Kirtland. Such claims are false and represent a misunderstanding about the marriage and divorce law of the day.

Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior…Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards.[1]

—Lynn Hunt, President of American Historical Association

Charges of statutory rape are inapplicable, since no such law or convention applied to any of Joseph's wives. Joseph's percentage of wives in their teen years was less than the series percentage of teen wives in Kirtland, Nauvoo, or the 1850 U.S. census, even among men his own age. If anything, Joseph married a greater percentage of older women, which suggests that motives other than sexual attraction drove these matches.

Large spousal age differences were not uncommon before and after Nauvoo, among members and non-members. To attack Joseph Smith on the age of his wives is to misunderstand the historic time in which he lived. Modern readers have been unfairly treated by authors who, misled by or preying upon presentism, either did not know, or declined to mention, that the practice was routine in Joseph’s time.

Critics of Joseph Smith are sometimes filled with righteous indignation when they raise the issue of his wives' ages. Never one to be over-burdened by historical details or interpretive nuance, vocal atheist Christopher Hitchens savages Joseph as a "serial practitioner of statutory rape." [2] Modern members and investigators, with more sincerity than Hitchens, have also been troubled (and even a little shocked) to learn, for example, that Joseph married one woman a few months shy of her fifteenth birthday.

Such surprise is a natural first reaction, though an author such as Hitchens—who purports to be providing reasoned analysis—might be expected to bring something besides knee-jerk slogans to the discussion. Sadly, Hitchens' remarks on religion generally provide little but bombast, so Latter-day Saints need not feel singled out. Hitchens does provide us, however, with a textbook example of presentism.

Imagine a school-child who asks why French knights didn't resist the English during the Battle of Agincourt (in 1415) using Sherman battle tanks. We might gently reply that there were no such tanks available. The child, a precocious sort, retorts that the French generals must have been incompetent, because everyone knows that tanks are necessary. The child has fallen into the trap of presentism—he has presumed that situations and circumstances in the past are always the same as the present. Clearly, there were no Sherman tanks available in 1415; we cannot in fairness criticize the French for not using something which was unavailable and unimagined.

Spotting such anachronistic examples of presentism is relatively simple. The more difficult problems involve issues of culture, behavior, and attitude. For example, it seems perfectly obvious to most twenty-first century North Americans that discrimination on the basis of race is wrong. We might judge a modern, racist politician quite harshly. We risk presentism, however, if we presume that all past politicians and citizens should have recognized racism, and fought it. In fact, for the vast majority of history, racism has almost always been present. Virtually all historical figures are, by modern standards, racists. To identify George Washington or Thomas Jefferson as racists, and to judge them as moral failures, is to be guilty of presentism.

A caution against presentism is not to claim that no moral judgments are possible about historical events, or that it does not matter whether we are racists or not. Washington and Jefferson were born into a culture where society, law, and practice had institutionalized racism. For them even to perceive racism as a problem would have required that they lift themselves out of their historical time and place. Like fish surrounded by water, racism was so prevalent and pervasive that to even imagine a world without it would have been extraordinarily difficult. We will not properly understand Washington and Jefferson, and their choices, if we simply condemn them for violating modern standards of which no one in their era was aware.

Hitchens' attack on Joseph Smith for "statutory rape" is a textbook example of presentist history. "Rape," of course, is a crime in which the victim is forced into sexual behavior against her (or his) will. Such behavior has been widely condemned in ancient and modern societies. Like murder or theft, it arguably violates the moral conscience of any normal individual. It was certainly a crime in Joseph Smith's day, and if Joseph was guilty of forced sexual intercourse, it would be appropriate to condemn him.

"Statutory rape," however, is a completely different matter. Statutory rape is sexual intercourse with a victim that is deemed too young to provide legal consent--it is rape under the "statute," or criminal laws of the nation. Thus, a twenty-year-old woman who chooses to have sex has not been raped. Our society has concluded, however, that a ten-year-old child does not have the physical, sexual, or emotional maturity to truly understand the decision to become sexually active. Even if a ten-year-old agrees to sexual intercourse with a twenty-year-old male, the male is guilty of "statutory rape." The child's consent does not excuse the adult's behavior, because the adult should have known that sex with a minor child is illegal.

Even in the modern United States, statutory rape laws vary by state. A twenty-year-old who has consensual sex with a sixteen-year-old in Alabama would have nothing to fear; moving to California would make him guilty of statutory rape even if his partner was seventeen.

By analogy, Joseph Smith likely owned a firearm for which he did not have a license--this is hardly surprising, since no law required guns to be registered on the frontier in 1840. It would be ridiculous for Hitchens to complain that Joseph "carried an unregistered firearm." While it is certainly true that Joseph's gun was unregistered, this tells us very little about whether Joseph was a good or bad man. The key question, then, is not "Would Joseph Smith's actions be illegal today?" Only a bigot would condemn someone for violating a law that had not been made.

Rather, the question should be, "Did Joseph violate the laws of the society in which he lived?" If Joseph did not break the law, then we might go on to ask, "Did his behavior, despite not being illegal, violate the common norms of conscience or humanity?" For example, even if murder was not illegal in Illinois, if Joseph repeatedly murdered, we might well question his morality.

We must, then, address four questions:

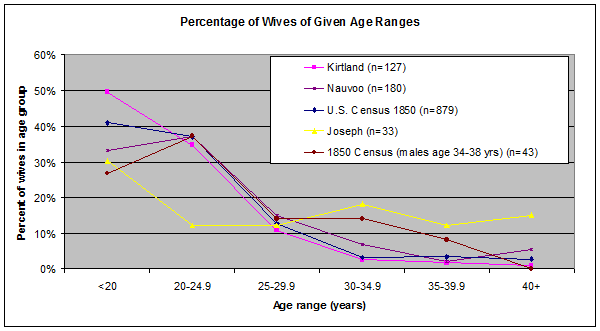

Even LDS authors are not immune from presentist fallacies: Todd Compton, convinced that plural marriage was a tragic mistake, "strongly disapprove[s] of polygamous marriages involving teenage women." [3] This would include, presumably, those marriages which Joseph insisted were commanded by God. Compton notes, with some disapproval, that a third of Joseph's wives were under twenty years of age. The modern reader may be shocked. We must beware, however, of presentism—is it that unusual that a third of Joseph's wives would have been teenagers?

When we study others in Joseph's environment, we find that it was not. A sample of 201 Nauvoo-era civil marriages found that 33.3% were under twenty, with one bride as young as twelve. [4] Another sample of 127 Kirtland marriages found that nearly half (49.6%) were under twenty. [5] And, a computer-aided study of LDS marriages found that from 1835–1845, 42.3% of women were married before age twenty. [6] The only surprising thing about Joseph's one third is that more of his marriage partners were not younger.

Furthermore, this pattern does not seem to be confined to the Mormons (see Chart 12 1). A 1% sample from the 1850 U.S. census found 989 men and 962 who had been married in the last year. Teens made up 36.0% of married women, and only 2.3% of men; the average age of marriage was 22.5 for women and 27.8 for men. [7] Even when the men in Joseph's age range (34–38 years) in the U.S. Census are extracted, Joseph still has a lower percentage of younger wives and more older wives than non-members half a decade later. [8]

I suspect that Compton goes out of his way to inflate the number of young wives, since he lumps everyone between "14 to 20 years old" together. [9] It is not clear why this age range should be chosen—women eighteen or older are adults even by modern standards.

A more useful breakdown by age is found in Table 12-1. Rather than lumping all wives younger than twenty-one together (a third of all the wives), our analysis shows that only a fifth of the wives would be under eighteen. These are the only women at risk of statutory rape issues even in the modern era.

| Age range | Percent (n=33) |

|---|---|

| 14-17 | 21.2% |

| 18-19 | 9.1% |

| 20-29 | 27.3% |

| 30-39 | 27.3% |

| 40-49 | 3.0% |

| 50-59 | 12.1% |

As shown elsewhere, the data for sexual relations in Joseph's plural marriages are quite scant (see Chapter 10—not online). For the purposes of evaluating "statutory rape" charges, only a few relationships are relevant.

The most prominent is, of course, Helen Mar Kimball, who was the prophet's youngest wife, married three months prior to her 15th birthday. [11] As we have seen, Todd Compton's treatment is somewhat confused, but he clarifies his stance and writes that "[a]ll the evidence points to this marriage as a primarily dynastic marriage." [12] Other historians have also concluded that Helen's marriage to Joseph was unconsummated. [13]

Nancy M. Winchester was married at age fourteen or fifteen, but we know nothing else of her relationship with Joseph. [14]

Flora Ann Woodruff was also sixteen at her marriage, and "[a]n important motivation" seems to have been "the creation of a bond between" Flora's family and Joseph. [15] We know nothing of the presence or absence of marital intimacy.

Fanny Alger would have been sixteen if Compton's date for the marriage is accepted. Given that I favor a later date for her marriage, this would make her eighteen. In either case, we have already seen how little reliable information is available for this marriage (see Chapter 4—not online), though on balance it was probably consummated.

Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Sarah Lawrence were each seventeen at the time of their marriage. Here at last we have reliable evidence of intimacy, since Lucy Walker suggested that the Lawrence sisters had consummated their marriage with Joseph. Intimacy in Joseph's marriages may have been more rare than many have assumed—Walker's testimony suggested marital relations with the Partridge and Lawrence sisters, but said nothing about intimacy in her own marriage (see Chapter 10—not online).

Sarah Ann Whitney's marriage had heavy dynastic overtones, binding Joseph to faithful Bishop Orson F. Whitney. We know nothing of a sexual dimension, though Compton presumes that one is implied by references to the couple's "posterity" and "rights" of marriage in the sealing ceremony. [16] This is certainly plausible, though the doctrine of adoption and Joseph's possible desire to establish a pattern for all marriages/sealings might caution us against assuming too much.

Of Joseph's seven under-eighteen wives, then, only one (Lawrence) has even second-hand evidence of intimacy. Fanny Alger has third-hand hostile accounts of intimacy, and we know nothing about most of the others. Lucy Walker and Helen Mar Kimball seem unlikely candidates for consummation.

The evidence simply does not support Christopher Hitchens' wild claim, since there is scant evidence for sexuality in the majority of Joseph's marriages. Many presume that Joseph practiced polygamy to satisfy sexual longings, and with a leer suggest that of course Joseph would have consummated these relationships, since that was the whole point. Such reasoning is circular, and condemns Joseph's motives and actions before the evidence is heard.

Even were we to conclude that Joseph consummated each of his marriages—a claim nowhere sustained by the evidence—this would not prove that he acted improperly, or was guilty of "statutory rape." This requires an examination into the legal climate of his era.

The very concept of a fifteen- or seventeen-year-old suffering statutory rape in the 1840s is flagrant presentism. The age of consent under English common law was ten. American law did not raise the age of consent until the late nineteenth century, and in Joseph Smith's day only a few states had raised it to twelve. Delaware, meanwhile, lowered the age of consent to seven. [17]

In our time, legal minors can often be married before the age of consent with parental approval. Joseph certainly sought and received the approval of parents or male guardians for his marriages to Fanny Alger, Sarah Ann Whitney, Lucy Walker, and Helen Kimball. [18] His habit of approaching male relatives on this issue might suggest that permission was gained for other marriages about which we know less.

Clearly, then, Hitchens' attack is hopelessly presentist. None of Joseph's brides was near ten or twelve. And even if his wives' ages had presented legal risks, he often had parental sanction for the match.

There can be no doubt that the practice of polygamy was deeply offensive to monogamous, Victorian America. As everything from the Nauvoo Expositor to the latest anti-Mormon tract shows, the Saints were continually attacked for their plural marriages.

If we set aside the issue of plurality, however, the only issue which remains is whether it would have been considered bizarre, improper, or scandalous for a man in his mid-thirties to marry a woman in her mid- to late-teens. Clearly, Joseph's marriage to teen-age women was entirely normal for Mormons of his era. The sole remaining question is, were all these teen-age women marrying men their own age, or was marriage to older husbands also considered proper?

To my knowledge, the issue of age disparity was not a charge raised by critics in Joseph's day. It is difficult to prove a negative, but the absence of much comment on this point is probably best explained by the fact that plural marriage was scandalous, but marriages with teenage women were, if not the norm, at least not uncommon enough to occasion comment. For example, to disguise the practice of plural marriage, Joseph had eighteen-year-old Sarah Whitney pretend to marry Joseph Kingsbury, who was days away from thirty-one. [19] If this age gap would have occasioned comment, Joseph Smith would not have used Kingsbury as a decoy.

One hundred and eighty Nauvoo-era civil marriages have husbands and wives with known ages and marriage dates. [20] Chart 12 2 demonstrates that these marriages follow the general pattern of wives being younger than husbands.

When the age of husband is plotted against the age of each wife, it becomes clear that almost all brides younger than twenty married men between five and twenty years older (see Chart 12-3).

This same pattern appears in 879 marriages from the 1850 U.S. Census (see Chart 12 4). Non-Mormon age differences easily exceeded Joseph's except for age fourteen. We should not make too much of this, since the sample size is very small (one or two cases for Joseph; three for the census) and dynastic motives likely played a large role in Joseph's choice, as discussed above.

In short, Mormon civil marriage patterns likely mimicked those of their gentile neighbors. Neither Mormons or their critics would have found broad age differences to be an impediment to conjugal marriage. In fact, the age difference between wives and their husbands was greatest in the teen years, and decreased steadily until around Joseph's age, between 30–40 years, when the spread between spouses' ages was narrowest (note the bright pink bars in Chart 12-5).

As Thomas Hine, a non-LDS scholar of adolescence noted:

Why did pre-modern peoples see nothing wrong with teen marriages? Part of the explanation likely lies in the fact that life-expectancy was greatly reduced compared to our time (see Table 12 2).

| Group | Life Expect in 1850 (years) [22] | Life Expect in 1901 (years) [23] | Life Expect in 2004 (years) [24] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males at birth | 38.3 | 47.9 | 75.7 |

| Males at age 20 | 60.1 | 62.0 | 76.6 |

| Females at birth | 40.5 | 50.7 | 80.8 |

| Females at age 20 | 60.2 | 63.6 | 81.5 |

The modern era has also seen the "extension" of childhood, as many more years are spent in schooling and preparation for adult work. In the 1840s, these issues simply weren't in play for women—men needed to be able to provide for their future family, and often had the duties of apprenticeship which prevented early marriage. Virtually everything a woman needed to know about housekeeping and childrearing, however, was taught in the home. It is not surprising, then, that parents in the 1840s considered their teens capable of functioning as married adults, while parents in 2007 know that marriages for young teens will usually founder on issues of immaturity, under-employment, and lack of education.

To see citations to the critical sources for these claims, click here

Notes

I knew he had three children. They told me.

- Mary Elizabeth Rollins Lightner[1]

To-day [Joseph] has not a soul descended from him personally, in this Church.

- George Q. Cannon[2]

While the record is frustratingly incomplete regarding sexuality, it does little but tease us when we consider whether Joseph fathered children by his plural wives. Fawn Brodie was the first to consider this question in any detail, though her standard of evidence was depressingly low. Subsequent authors have returned to the problem, though unanimity has been elusive (see Table 1). Ironically, Brodie did not even mention the case of Josephine Lyon, now considered the most likely potential child of Joseph.

Table 11‑1 Possible Children of Joseph Smith, Jr., by Plural Marriage[3]

[4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39]

DNA analysis has determined that Josephine Fisher is not a descendant of Joseph Smith, Jr., [40] but for many years she appeared to be the strongest possibility. The resolution of this question was difficult to resolve until the appropriate DNA analysis techniques became available. These findings have been replicated in non-Latter-day Saint, peer-reviewed, reputable journals.[41]

The case of Josephine Fisher relied on a deathbed conversation:

Just prior to my mothers death in 1882 she called me to her bedside and told me that her days were about numbered and before she passed away from mortality she desired to tell me something which she had kept as an entire secret from me and from all others but which she now desired to communicate to me. She then told me that I was the daughter of the Prophet Joseph Smith….[42]

Perhaps significantly, Josephine's name shares a clear link with Joseph's. Whether this account proved that she was his biological daughter had long been debated:

Rex Cooper…has questioned the interpretation that Smith was Fisher's biological father. He posits that because Fisher's mother was sealed to Smith, Fisher was his daughter only in a spiritual sense…More problematic is whether there is a discrepancy between what Fisher understood and what her mother meant. That is, did Fisher interpret her mother's remarks to mean she was the biological daughter of Joseph Smith and thus state that with more certitude than was warranted, when in fact her mother meant only that in the hereafter Fisher would belong to Joseph Smith's family through Session's sealing to him? Because Sessions was on her deathbed, when one's thoughts naturally turn to the hereafter, the latter is a reasonable explanation.[43]

As Danel Bachman notes, however, there seems to be relatively little doubt that

[t]he desire for secrecy as well as the delicacy of the situation assure us that Mrs. Sessions was not merely explaining to her daughter that she was Smith's child by virtue of a temple sealing. The plain inference arising from Jenson's curiosity in the matter and Mrs. Fisher's remarks is that she was, in fact, the offspring of Joseph Smith.[44]

However, DNA evidence now disproves this theory. It is possible, then, that Fisher misunderstood her mother, but this seems unlikely. Any unreliability is more likely to arise because of a dying woman's confusion than from miscommunication. No evidence exists for such confusion, though we cannot rule it out.

Josephine's account is also noteworthy because her mother emphasizes that "…she [had] been sealed to the Prophet at the time that her husband Mr. Lyon was out of fellowship with the Church."[45] This may explain her reasoning for being sealed to Joseph at all—her husband was out of fellowship. Todd Compton opines that "[i]t seems unlikely that Sylvia would deny [her husband] cohabitation rights after he was excommunicated," but this conclusion seems based on little but a gut reaction.[46] These women took their religion seriously; given Sylvia's deathbed remarks, this was a point she considered important enough to emphasize. She apparently believed it would provide an explanation for something that her daughter might have otherwise misunderstood.

There is also clear evidence that at least some early members of the Church would have taken a similar attitude toward sexual relations with an unbelieving spouse. My own third-great grandfather, Isaiah Moses Coombs, provides a striking illustration of this from the general membership of the Church.

Coombs had immigrated to Utah, but his non-member spouse refused to accompany him. Heartsick, he consulted Brigham Young for advice. Young "sat with one hand on my knee, looking at my face and listen[ing] attentively." Then, Young took the new arrival "by the hand in his fatherly way," and said "[Y]ou had better take a mission to the States…to preach the gospel and visit your wife…visit your wife as often as you please; preach the gospel to her, and if she is worth having she will come with you when you return to the valley. God bless and prosper you."[47]

Coombs did as instructed, but was not successful in persuading his wife. His description of his thoughts is intriguing, and worth quoting at length:

I may as well state here, however, that during all my stay in the States, [my wife and I] were nothing more to each other than friends. I never proposed or hinted for a closer intimacy only on condition of her baptism into the Church. I felt that I could not take her as a wife on any other terms and stand guiltless in the sight of God or my own conscience…I could not yield to her wishes and she would not bend to mine. And so I merely visited her as a friend. This was a source of wonder to our mutual acquaintances; and well it might be for had not my faith been founded on the eternal rock of Truth, I never could have stood such a test, I never could have withstood the temptations that assailed me, but I should have yielded and have abandoned myself to the life of carnal pleasure that awaited me in the arms of my beautiful and adored wife. She was now indeed beautiful. I had thought her lovely as a child—as a maiden she had seemed to me surpassing fair, but as a woman with a form well developed and all the charms of her persona matured, she far surpassed in womanly beauty anything I had ever dreamed of.[48]

Coombs' account is startlingly blunt and explicit for the age. Yet, if this young twenty-two-year-old male refused marital intimacy with his wife (whom he married knowing their religious differences), Compton's confidence that Sylvia Sessions would not deny marital relations to her excommunicated husband seems misplaced. Sessions may, like Coombs, have seen her faithfulness to the sealing ordinances sufficient to "eventually either in this life or that which is to come enable me to bind my [spouse] to me in bands that could not be broken." Like him, she may have believed that "[My spouse] was blind then but the day would come when [he] would see."[49]

More importantly, however, is Brian Hales’ more recent work, which demonstrates that Sylvia Sessions Lyon may well have not been married to her husband when sealed to Joseph Smith, contrary to Compton’s conclusion. Thus, rather than being a case of polyandry with sexual relations with two men (Joseph and her first husband) Lyons is instead a case of straight-forward plural marriage.[50] Given that Joseph has been ruled out as Josephine's father, it may be that Sylvia's emphasis to Josephine about being Joseph's "daughter" referred to a spiritual or sealing sense, and she wished to explain to her daughter why Josephine was, then, sealed to Joseph Smith rather than her biological father.

Olive Gray Frost is mentioned in two sources as having a child by Joseph. Both she and the child died in Nauvoo, so no genetic evidence will ever be forthcoming.[51]

Angus M. Cannon seems to have been aware of Fisher's claim to be a child of Joseph Smith, though only second hand. He told a sceptical Joseph Smith III of

one case where it was said by the girl's grandmother that your father has a daughter born of a plural wife. The girl's grandmother was Mother Sessions, who lived in Nauvoo and died here in the valley. Aunt Patty Sessions asserts that the girl was born within the time after your father was said to have taken the mother.[52]

Clearly, Cannon has no independent knowledge of the case, but reports a story similar to Josephine's affidavit. Cannon's statement is more important because it illustrates how the LDS Church's insistence that Joseph Smith had practiced plural marriage led some of the RLDS Church :to ask why no children by these wives existed. Lucy Walker reported [the RLDS] seem surprised that there was no issue from asserted plural marriages with their father. Could they but realize the hazardous life he lived, after that revelation was given, they would comprehend the reason. He was harassed and hounded and lived in constant fear of being betrayed by those who ought to have been true to him.[53] Thus the absence of children was something of an embarrassment to the Utah Church, which members felt a need to explain. It would have been greatly to their advantage to produce Joseph's offspring, but could not.[54]

Anxious to demonstrate that Joseph's plural marriages were marriages in the fullest sense, Lucy M. Walker (wife of Joseph's cousin, George A. Smith) reported seeing Joseph washing blood from his hands in Nauvoo. When asked about the blood, Joseph reportedly told her he had been helping Emma deliver one of his plural wives' children.[55] Yet, even this late account tells us little about the paternity of the children—Joseph was close to these women (and their husbands, in the case of polyandry), and given the Saints' belief in priesthood blessings, they may have well welcomed his involvement.

Even by the turn of the century, the LDS Church had no solid evidence of children by Joseph. "I knew he had three children," said Mary Elizabeth Lightner, "They told me. I think two of them are living today but they are not known as his children as they go by other names."[56] Again, evidence for children is frustratingly vague—Lightner had only heard rumours, and could not provide any details. It would seem to me, however, that this remark of Lightner's rules out her children as possible offspring of Joseph. Her audience was clearly interested in Joseph having children, and she was happy to assert that such children existed. If her own children qualified, why did she not mention them?

Two of Marinda Nancy Johnson Hyde's children have been suggested as possible children. The first, Orson, died in infancy, making DNA testing impossible. Compton notes, however, that "Marinda had no children while Orson was on his mission to Jerusalem, then became pregnant soon after Orson returned home. (He arrived in Nauvoo on December 7, 1842, and Marinda bore Orson Washington Hyde on November 9, 1843),"[57] putting the conception date around 16 February 1843.

Frank Hyde's birth date is unclear; he was born on 23 January in either 1845 or 1846.[58] This would place his conception around 2 May, of either 1844 or 1845. In the former case, Frank was conceived less than two months prior to Joseph's martyrdom. Orson Hyde left for Washington, D.C., around 4 April 1844,[59] and did not return until 6 August 1844, making Joseph's paternity more likely than Orson's if the earlier birth date is correct.[60] The key source for this claim is Fawn Brodie, who includes no footnote or reference. Given Brodie's tendency to misread evidence on potential children, this claim should be approached with caution.

Frank's death certificate lists Orson Hyde as the father, however, and places his birth in 1846, which would require conception nearly a year after Joseph's death.[61] A child by Joseph would have brought prestige to the family and Church, and Orson and Nancy had divorced long before Frank Henry's death.[62] It seems unlikely, therefore, that Orson would be credited with paternity over Joseph if any doubt existed. Without further data, Brodie's dating should probably be regarded as an error, ruling out Joseph as a possible father.

Scientific ingenuity has also been applied to the question of Joseph's paternity. Y-chromosome studies have conclusively eliminated Orrison Smith (son of Fanny Alger), Mosiah Hancock, Zebulon Jacobs, John Reed Hancock, Moroni Llewellyn Pratt, and Oliver Buell as Joseph's offspring.[63]

Two additional children—George Algernon Lightner and Orson W. Hyde—died in infancy, leaving no descendants to test, though as noted above Lightner can probably be excluded on the basis of his mother's testimony.

The testing of female descendants' DNA is much move involved, but work continues and may provide the only definitive means of ruling in or out potential children.

The case of Oliver Buell is an interesting one, since Fawn Brodie was insistent that he was Joseph's son. She based part of this argument on a photograph of Buell, which revealed a face which she claimed was "overwhelmingly on the side of Joseph's paternity."[64] A conception on this date would make Oliver two to three weeks overdue at birth, which makes Brodie's theory less plausible.[65]

Furthermore, prior the DNA results, Bachman and Compton pointed out that Brodie's timeline poses serious problems for her theory—Oliver's conception would have had to occurred between 16 April 1839 (when Joseph was allowed to escape during a transfer from Liberty Jail)[66] and 18 April, when the Huntingtons left Far West.[67] Brodie would have Joseph travel west from his escape near Gallatin, Davies County, Missouri, to Far West in order to meet Lucinda, and then on to Illinois to the east. This route would require Joseph and his companions to backtrack, while fleeing from custody in the face of an active state extermination order in force.[68] Travel to Far West would also require them to travel near the virulently anti-Mormon area of Haun's Mill, along Shoal Creek.[69] Yet, by 22 April Joseph was in Illinois, having been slowed by travel "off from the main road as much as possible"[70] "both by night and by day."[71] This seems an implausible time for Joseph to be meeting a woman, much less conceiving a child. Furthermore, it is evident that Far West was evacuated by other Church leaders, "the committee on removal," and not under the prophet’s direction, who did not regain the Saints until reaching Quincy, Illinois.[72]

Brodie's inclusion of Oliver Buell is also inconsistent, since he was born prior to Joseph's sealing to Prescinda. By including Oliver as a child, Brodie wishes to paint Joseph as an indiscriminate womanizer. Yet, her theory of plural marriage argues that Joseph "had too much of the Puritan in him, and he could not rest until he had redefined the nature of sin and erected a stupendous theological edifice to support his new theories on marriage."[73] Thus, Brodie argues that Joseph created plural marriage to justify his immorality—yet, she then has him conceiving a child with Prescinda before being sealed to her. By her own argument, the paternity must therefore be seen as doubtful.[74]

Despite Brodie's enthusiasm, no other author has included Oliver on their list of possible children (see Table 1). And, DNA evidence has conclusively ruled him out. Oliver is an excellent example of Brodie's tendency to ignore and misread evidence which did not fit her preconceptions, and suggests that caution is warranted before one condemns Joseph for a pre-plural marriage "affair" or other improprieties. Since Brodie was not interested in giving Joseph the benefit of the doubt, or avoiding a rush to judgment, her decision is not surprising.

John Reed Hancock is another of Brodie's suggestions, though no other author has followed her. The evidence for Joseph having married Clarissa Reed Hancock is scant,[75] and as with Oliver Buell it is unlikely (even under Brodie's jaded theory of plural marriage as justification for adultery) that Joseph would have conceived a child with a woman to whom he was not polygamously married. DNA testing has since confirmed our justified scepticism of Brodie's claim.[76]

Bachman mentions a "seventh child" of Prescinda's, likely John Hyrum Buell, for whom the timeline would better accommodate conception by Joseph Smith. There is no other evidence for Joseph's paternity, however, save Ettie V. Smith's account in the anti-Mormon Fifteen Years Among the Mormons (1859), which claimed that Prescinda said she did not know whether Joseph or her first husband was John Hyrum's father.[77] As Compton notes, such an admission is implausible, given the mores of the time.[78]

Besides being implausible, Ettie gets virtually every other detail wrong—she insists that William Law, Robert Foster, and Henry Jacobs had all been sent on missions, only to return and find their wives being courted by Joseph. Ettie then has them establish the Expositor.[79] While Law and Foster were involved with the Expositor, they were not sent on missions, and their wives did not charge that Joseph had propositioned them. Jacobs had served missions, but was present during Joseph's sealing to his wife, and did not object (see Chapter 9). Jacobs was a faithful Saint unconnected to the Expositor.

Even the anti-Mormon Fanny Stenhouse considered Ettie Smith to be a writer who "so mixed up fiction with what was true, that it was difficult to determine where one ended and the other began,"[80] and a good example of how "the autobiographies of supposed Mormon women were [as] unreliable"[81] as other Gentile accounts, given her tendency to "mingl[e] facts and fiction" "in a startling and sensational manner."[82]

Brodie herself makes no mention of John Hyrum as a potential child (and carelessly misreads Ettie Smith's remarks as referring to Oliver, not John Hyrum). No other historian has even mentioned this child, much less argued that Buell was not the father (see Table 1).

A few other possibilities should be mentioned, though the evidence surrounding them is tenuous. Sarah Elizabeth Holmes was born to Marietta Carter, though “No evidence links her with Joseph Smith.”[83] The Dibble children suffer from chronology problems, and a lack of good evidence that Joseph and their mother was associated. Loren Dibble was, however, claimed by some Mormons as a child of Joseph’s when confronted with Joseph Smith III’s skepticism.[84]

Joseph Albert Smith was born to Esther Dutcher, but the available evidence supports her polyandrous sealing to Joseph as for eternity only. Carolyn Delight has no evidence at all of a connection to Joseph—the only source is a claim to Ugo Perego, a modern DNA researcher.[85] No textual or documentary evidence is known for her at all.

We have elsewhere seen the tenuous basis for many conclusions about the Fanny Alger marriage (see here and here). The first mention of a pregnancy for Fanny is in an 1886 anti-Mormon work, citing Chauncey Webb, with whom Fanny reportedly lived after leaving the Smith home.[86] Webb claimed that Emma "drove" Fanny from the house because she "was unable to conceal the consequences of her celestial relation with the prophet." If Fanny was pregnant, it is curious that no one else remarked upon it at the time, though it is possible that the close quarters of a nineteenth-century household provided Emma with clues. If Fanny was pregnant by Joseph, the child never went to term, died young, or was raised under a different name.

A family tradition—repeated by anti-Mormon Wyl—holds that Eliza R. Snow was pregnant and shoved down the stairs by a jealous Emma before being required to leave the Smith home.[87] The tradition holds that Eliza, "heavy with child" subsequently miscarried. While Eliza was required to leave the home and Emma was likely upset with her, no contemporary evidence points to a pregnancy.[88] Eliza's diary says nothing about the loss of a child, which would be a strange omission given her love of children.[89] It seems unlikely that Eliza would have still been teaching school in an advanced state of pregnancy, especially given that her appearance as a pregnant "unwed mother" would have been scandalous in Nauvoo. Emma's biographers note that "Eliza continued to teach school for a month after her abrupt departure from the Smith household. Her own class attendance record shows that she did not miss a day during the months she taught the Smith children, which would be unlikely had she suffered a miscarriage."[90] Given Emma's treatment of the Partridge sisters, who were also required to leave the Smith household, Emma certainly needed no pregnancy to raise her ire against Joseph's plural wives.

Eliza repeatedly testified to the physical nature of her relationship with Joseph Smith (see Chapter 9), and was not shy about criticizing Emma on the subject of plural marriage.[91] Yet, she never reported having been pregnant, or used her failed pregnancy as evidence for the reality of plural marriage.

In the absence of further information, both of these reported pregnancies must be regarded as extremely speculative.

Few authors agree on which children should even be considered as Joseph's potential children. Candidates which some find overwhelmingly likely are dismissed—or even left unmentioned—by others. Recent scholars have included between one to four potential children as options. Of these, Josephine Lyon was the most persuasive, until her relationship to Joseph Smith was ultimately disproven through DNA testing. Orson W. Hyde died in infancy, and so can never be definitively excluded as a possible child, though the dates of conception argue against Joseph's paternity. Oliver Gray Frost is mentioned in two sources as having a child by Joseph. Both she and the child died in Nauvoo, so no genetic evidence will ever be forthcoming.[92]

This table is in the same order as Table 1.[93]

Brodie;[94] Bachman;[95]; and Compton.[96]

As always, we are left where we began—with more suspicions and possibilities than certitudes. One's attitude toward Joseph and the Saints will influence, more than anything else, how these conflicting data are interpreted.

The uncertainty surrounding Joseph's offspring is even more astonishing when we appreciate how much such a child would have been valued. The Utah Church of the 19th century was anxious to prove that Joseph had practiced full plural marriage, and that their plural families merely continued what he started. Any child of Joseph's would have been treasured, and the family honoured. There was a firm expectation that even Joseph's sons by Emma would have an exalted place in the LDS hierarchy if they were to repent and return to the Church.[97] As Alma Allred noted, "Susa Young Gates indicated that [Brigham Young] wasn’t aware of such a child when she wrote that her father and the other apostles were especially grieved that Joseph did not have any issue in the Church."[98]

In 1884, George Q. Cannon bemoaned this lack of Joseph's posterity:

There may be faithful men who will have unfaithful sons, who may not be as faithful as they might be; but faithful posterity will come, just as I believe it will be the case with the Prophet Joseph's seed. To-day he has not a soul descended from him personally, in this Church. There is not a man bearing the Holy Priesthood, to stand before our God in the Church that Joseph was the means in the hands of God, of founding—not a man to-day of his own blood,—that is, by descent,—to stand before the Lord, and represent him among these Latter-day Saints.[99]

Brigham and Cannon, a member of the First Presidency, would have known of Joseph's offspring if any of the LDS leadership did. Yet, despite the religious and public relations value which such a child would have provided, they knew of none. It is possible that Joseph had children by his plural wives, but by no means certain. The data are surprisingly ephemeral.

- Some wonder if sexual relations were included in Joseph Smith’s plural marriages. The answer is yes or no, depending upon the type of plural marriage. Those marriages, often called “sealings,” were of two types. Some were for this life and the next (called “time-and-eternity”) and could include sexuality on earth. Others were limited to the next life (called “eternity-only”) and did not allow intimacy in mortality. Overall, evidence indicates that less than half of Joseph Smith’s polygamous unions were consummated and sexual relations in the others occurred infrequently. (Link)

It appears the Prophet experienced sexual relations with less than half of the women sealed to him. There is no credible evidence that Joseph had sex with three subgroups of his plural wives: (1) fourteen-year-old wives, (2) non-wives (or women to whom he was not married), and (3) legally married women who were experiencing conjugal relations with their civil husbands. (Link)

No children are known to have been born to Joseph and his plural wives. (Link)

Notes

FAIR Answers—back to home page

| Polyandry | John C. Bennett Prior to Nauvoo |

- Joseph's first plural marriage after Fanny Alger. (Link)

Joseph Smith made his second proposal to a previously unmarried woman in Nauvoo and the first proposal since his marriage to Louisa Beaman. (Link)

John C. Bennett arrived in Nauvoo in September of 1840 and stayed less than two years. In spite of his relatively brief time living among the Saints, his impact upon the secret expansion of plural marriage was immense. (Link)

One unmarried woman Joseph approached was Nancy Rigdon, the nineteen-year-old daughter of his First Counselor in the First Presidency, Sidney Rigdon. The proposal turned out badly. (Link)

William Marks related that Joseph’s conversation denouncing plural marriage occurred “three weeks before his death” or around June 6. Perhaps Joseph had such a change of heart during the first week of June, but this seems unlikely and other parts of Marks’ recollection are implausible. (Link)

</onlyinclude>

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now